I wrote a (very long) blog post about those viral math problems and am looking for feedback, especially from people who are not convinced that the problem is ambiguous.

It’s about a 30min read so thank you in advance if you really take the time to read it, but I think it’s worth it if you joined such discussions in the past, but I’m probably biased because I wrote it :)

If you are so sure that you are right and already “know it all”, why bother and even read this? There is no comment section to argue.

I beg to differ. You utter fool! You created a comment section yourself on lemmy and you are clearly wrong about everything!

You take the mean of 1 and 9 which is 4.5!

/j

Right, because 5 rounds down to 4.5

@Prunebutt meant 4.5! and not 4.5. Because it’s not an integer we have to use the gamma function, the extension of the factorial function to get the actual mean between 1 and 9 => 4.5! = 52.3428 which looks about right 🤣

🤣 I wasn’t even sure if I should post it on lemmy. I mainly wrote it so I can post it under other peoples posts that actually are intended to artificially create drama to hopefully show enough people what the actual problems are with those puzzles.

But I probably am a fool and this is not going anywhere because most people won’t read a 30min article about those math problems :-)

Actually the correct answer is clearly 0.2609 if you follow the order of operations correctly:

6/2(1+2)

= 6/23

= 0.26🤣 I’m not sure if you read the post but I also wrote about that (the paragraph right before “What about the real world?”)

I did read the post (well done btw), but I guess I must have missed that. And here I thought I was a comedic genius

I would do the mighty parentheses first, and then the 2 that dares to touch the mighty parentheses, finally getting to the run-of-the-mill division. Hence the answer is One.

Honestly, I do disagree that the question is ambiguous. The lack of parenthetical separation is itself a choice that informs order of operations. If the answer was meant to be 9, then the 6/2 would be isolated in parenthesis.

It’s covered in the blog, but this is likely due to a bias towards Strong Juxtaposition rules for parentheses rather than Weak. It’s common for those who learned math into advanced algebra/ beginning Calc and beyond, since that’s the usual method for higher math education. But it isn’t “correct”, it’s one of two standard ways of doing it. The ambiguity in the question is intentional and pervasive.

My argument is specifically that using no separation shows intent for which way to interpret and should not default to weak juxtaposition.

Choosing not to use (6/2)(1+2) implies to me to use the only other interpretation.

There’s also the difference between 6/2(1+2) and 6/2*(1+2). I think the post has a point for the latter, but not the former.

I originally had the same reasoning but came to the opposite conclusion. Multiplication and division have the same precedence, so I read the operations from left to right unless noted otherwise with parentheses. Thus:

6/2=3

3(1+2)=9

For me to read the whole of 2(1+2) as the denominator in a fraction I would expect it to be isolated in parentheses: 6/(2(1+2)).

Reading the blog post, I understand the ambiguity now, but i’m still fascinated that we had the same criticism (no parentheses implies intent) but had opposite conclusions.

6/2=3

3(1+2)=9

You just did division before brackets, which goes against order of operations rules.

For me to read the whole of 2(1+2) as the denominator in a fraction

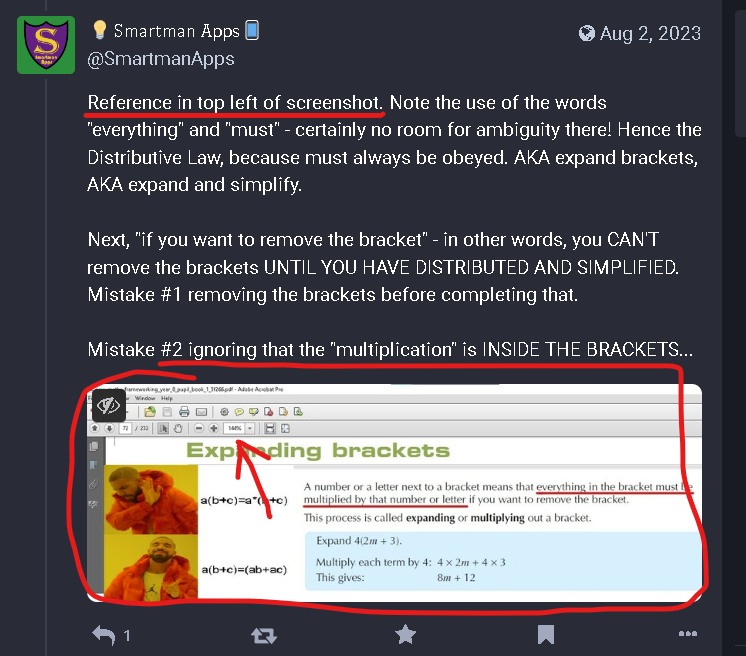

You just need to know The Distributive Law and Terms.

Read the linked article

The linked article is wrong. Read this - has, you know, actual Maths textbook references in it, unlike the article.

I don’t know what you want, man. The blog’s goal is to describe the problem and why it comes about and your response is “Following my logic, there is no confusion!” when there clearly is confusion in the wider world here. The blog does a good job of narrowing down why there’s confusion, you’re response doesn’t add anything or refute anything. It’s just… you bragging? I’m not certain what your point is.

your response is “Following my logic, there is no confusion!”

That’s because the actual rules of Maths have all been followed, including The Distributive Law and Terms.

there clearly is confusion in the wider world here

Amongst people who don’t remember The Distributive Law and Terms.

The blog does a good job of narrowing down why there’s confusion

The blog ignores The Distributive Law and Terms. Notice the complete lack of Maths textbook references in it?

But it isn’t “correct”

It is correct - it’s The Distributive Law.

it’s one of two standard ways of doing it.

There’s only 1 way - the “other way” was made up by people who don’t remember The Distributive Law and/or Terms (more likely both), and very much goes against the standards.

The ambiguity in the question is

…zero.

Hooray! Correct! Anyone who downvoted or disagrees with this needs to read this instead. Includes actual Maths textbooks references.

Did you read the blog post?

@wischi “Funny enough all the examples that N.J. Lennes list in his letter use implicit multiplications and thus his rule could be replaced by the strong juxtaposition”.

Weird they didn’t need two made-up terms to get it right 100 years ago.

Indeed Duncan. :-)

his rule could be replaced by the strong juxtaposition

“strong juxtaposition” already existed even then in Terms (which Lennes called Terms/Products, but somehow missed the implication of that) and The Distributive Law, so his rule was never adopted because it was never needed - it was just Lennes #LoudlyNotUnderstandingThings (like Terms, which by his own admission was in all the textbooks). 1917 (ii) - Lennes’ letter (Terms and operators)

In other words…

Funny enough all the examples that N.J. Lennes list in his letter use

…Terms/Products., as we do today in modern high school Maths textbooks (but we just use Terms in this context, not Products).

Nope it’s bedmas since everything is brackets

I’ve seen a calculator interpret 1 ÷ 2π as ½π which was kinda funny

An e-calculator I’m guessing? (either that or Texas Instruments) Desmos USED TO interpret that correctly, but then they made a change with automatically turning division into fractions and broke it (because if you’ve specified division then it’s not a fraction) dotnet.social/@SmartmanApps/111164851485070719

I believe it was a app , yes

All calculators that are listed in the article as following weak juxtaposition would interpreted it that way.

And they’re all wrong dotnet.social/@SmartmanApps/111164851485070719

The ambiguous ones at least have some discussion around it. The ones I’ve seen thenxouple times I had the misfortune of seeing them on Facebook were just straight up basic order of operations questions. They weren’t ambiguous, they were about a 4th grade math level, and all thenpeople from my high-school that complain that school never taught them anything were completely failing to get it.

I’m talking like 4+1x2 and a bunch of people were saying it was 10.

While I agree the problem as written is ambiguous and should be written with explicit operators, I have 1 argument to make. In pretty much every other field if we have a question the answer pretty much always ends up being something along the lines of “well the experts do this” or “this professor at this prestigious university says this”, or “the scientific community says”. The fact that this article even states that academic circles and “scientific” calculators use strong juxtaposition, while basic education and basic calculators use weak juxtaposition is interesting. Why do we treat math differently than pretty much every other field? Shouldn’t strong juxtaposition be the precedent and the norm then just how the scientific community sets precedents for literally every other field? We should start saying weak juxtaposition is wrong and just settle on one.

This has been my devil’s advocate argument.

While I agree the problem as written is ambiguous

It’s not.

the answer pretty much always ends up being something along the lines of “well the experts do this” or “this professor at this prestigious university says this”, or “the scientific community says”.

Agree completely! Notice how they ALWAYS leave out high school Maths teachers and textbooks? You know, the ones who actually TEACH this topic. Always people OTHER THAN the people/books who teach this topic (and so always end up with the wrong conclusion).

while basic education and basic calculators use weak juxtaposition

Literally no-one in education uses so-called “weak juxtaposition” - there’s no such thing. There’s The Distributive Law and Terms, both of which use so-called “strong juxtaposition”. Most calculators do too.

Shouldn’t strong juxtaposition be the precedent and the norm

It is. In fact it’s the rules (The Distributive Law and Terms).

We should start saying weak juxtaposition is wrong

Maths teachers already DO say it’s wrong.

This has been my devil’s advocate argument.

No, this is mostly a Maths teacher argument. You started off weak (saying its ambiguous), but then after that almost everything you said is actually correct - maybe you should be a Maths teacher. :-)

I don’t remember everything, but I remember the first two operations are exponents then parentheses. Edit: wait is it the other way around?

Yes it’s the other way round. Parentheses are top priority.

bidmas

brackets, index (powers), division, multiplication, addition, subtraction.

brackets are always first that’s the whole point of brackets

The full story is actually more nuanced than most people think, but the post is actually very long (about 30min) so thank you in advance if you really find the time to read it.

Having read your article, I contend it should be:

P(arentheses)

E(xponents)

M(ultiplication)D(ivision)

A(ddition)S(ubtraction)

and strong juxtaposition should be thrown out the window.Why? Well, to be clear, I would prefer one of them die so we can get past this argument that pops up every few years so weak or strong doesn’t matter much to me, and I think weak juxtaposition is more easily taught and more easily supported by PEMDAS. I’m not saying it receives direct support, but rather the lack of instruction has us fall back on what we know as an overarching rule (multiplication and division are equal). Strong juxtaposition has an additional ruling to PEMDAS that specifies this specific case, whereas weak juxtaposition doesn’t need an additional ruling (and I would argue anyone who says otherwise isn’t logically extrapolating from the PEMDAS ruleset). I don’t think the sides are as equal as people pose.

To note, yes, PEMDAS is a teaching tool and yes there are obviously other ways of thinking of math. But do those matter? The mathematical system we currently use will work for any usecase it does currently regardless of the juxtaposition we pick, brackets/parentheses (as well as better ordering of operations when writing them down) can pick up any slack. Weak juxtaposition provides better benefits because it has less rules (and is thusly simpler).

But again, I really don’t care. Just let one die. Kill it, if you have to.

Division comes before Multiplication, doesn’t it? I know BODMAS.

That makes no sense. Division is just multiplication by an inverse. There’s no reason for one to come before another.

This actually explains alot. Murica is Pemdas but Canadian used Bodmas so multiply is first in America.

As far as I understand it, they’re given equal weight in the order of operations, it’s just whichever you hit first left to right.

Ah, but if you use the rules BODMSA (or PEDMSA) then you can follow the letter order strictly, ignoring the equal precedence left-to-right rule, and you still get the correct answer. Therefore clearly we should start teaching BODMSA in primary schools. Or perhaps BFEDMSA. (Brackets, named Functions, Exponentiation, Division, Multiplication, Subtraction, Addition). I’m sure that would remove all confusion and stop all arguments. … Or perhaps we need another letter to clarify whether implicit multiplication with a coefficient and no symbol is different to explicit multiplication… BFEIDMSA or BFEDIMSA. Shall we vote on it?

Don’t need any extra letters - just need people to remember the rules around expanding brackets in the first place.

Obviously more letters would make the mnemonic worse, not better. I was making a joke.

As for the brackets ‘the rules around expanding brackets’ are only meaningful in the assumed context of our order of operations. For example, if we instead all agreed that addition should be before multiplication, then a×(b+c) would “expand” to a×b+c, because the addition is before multiplication anyway and the brackets do nothing.

I was making a joke.

Fair enough, but my point still stands.

if we instead all agreed that addition should be before multiplication

…then you would STILL have to do multiplication first. You can’t change Maths by simply agreeing to change it - that’s like saying if we all agree that the Earth is flat then the Earth is flat. Similarly we can’t agree that 1+1=3 now. Maths is used to model the real world - you can’t “agree” to change physics. You can’t add 1 thing to 1 other thing and have 3 things now, no matter how much you might want to “agree” that there is 3, there’s only 2 things. Multiplying is a binary operation, and addition is unary, and you have to do binary operators before unary operators - that is a fact that no amount of “agreeing” can change. 2x3 is actually a contracted form of 2+2+2, which is why it has to be done before addition - you’re in fact exposing the hidden additions before you do the additions.

the brackets do nothing

The brackets, by definition, say what to do first. Regardless of any other order of operations rules, you always do brackets first - that is in fact their sole job. They indicate any exceptions to the rules that would apply otherwise. They perform no other function. If you’re going to no longer do brackets first then you would simply not use them at all anymore. And in fact we don’t - when there are redundant brackets, like in (2)(1+2), we simply leave them out, leaving 2(1+2).

Yeah 100% was not taught that. Follow the pemdas or fail the test. Division is after Multiply in pemdas.

I put the equation into excel and get 9 which only makes sense in bodmas.

I think anything after (whichever grade your country introduces fractions in) should exclusively use fractions or multiplication with fractions to express division in order to disambiguate. A division symbol should never be used after fractions are introduced.

This way, it doesn’t really matter which juxtaposition you prefer, because it will never be ambiguous.

Anything before (whichever grade introduces fractions) should simply overuse brackets.

This comment was written in a couple of seconds, so if I missed something obvious, feel free to obliterate me.

A division symbol should never be used after fractions are introduced.

But a fraction is a single term, 2 numbers separated by a division is 2 terms. Terms are separated by operators and joined by grouping symbols.

I think weak juxtaposition is more easily taught

Except it breaks the rules which already are taught.

the PEMDAS ruleset

But they’re not rules - it’s a mnemonic to help you remember the actual order of operations rules.

Just let one die. Kill it, if you have to

Juxtaposition - in either case - isn’t a rule to begin with (the 2 appropriate rules here are The Distributive Law and Terms), yet it refuses to die because of incorrect posts like this one (which fails to quote any Maths textbooks at all, which is because it’s not in any textbooks, which is because it’s wrong).

Except it breaks the rules which already are taught.

It isn’t, because the ‘currently taught rules’ are on a case-by-case basis and each teacher defines this area themselves. Strong juxtaposition isn’t already taught, and neither is weak juxtaposition. That’s the whole point of the argument.

But they’re not rules - it’s a mnemonic to help you remember the actual order of operations rules.

See this part of my comment: “To note, yes, PEMDAS is a teaching tool and yes there are obviously other ways of thinking of math. But do those matter? The mathematical system we currently use will work for any usecase it does currently regardless of the juxtaposition we pick, brackets/parentheses (as well as better ordering of operations when writing them down) can pick up any slack. Weak juxtaposition provides better benefits because it has less rules (and is thusly simpler).”

Juxtaposition - in either case - isn’t a rule to begin with (the 2 appropriate rules here are The Distributive Law and Terms), yet it refuses to die because of incorrect posts like this one (which fails to quote any Maths textbooks at all, which is because it’s not in any textbooks, which is because it’s wrong).

You’re claiming the post is wrong and saying it doesn’t have any textbook citation (which is erroneous in and of itself because textbooks are not the only valid source) but you yourself don’t put down a citation for your own claim so… citation needed.

In addition, this issue isn’t a mathematical one, but a grammatical one. It’s about how we write math, not how math is (and thus the rules you’re referring to such as the Distributive Law don’t apply, as they are mathematical rules and remain constant regardless of how we write math).

It isn’t, because the ‘currently taught rules’ are on a case-by-case basis and each teacher defines this area themselves

Nope. Teachers can decide how they teach. They cannot decide what they teach. The have to teach whatever is in the curriculum for their region.

Strong juxtaposition isn’t already taught, and neither is weak juxtaposition

That’s because neither of those is a rule of Maths. The Distributive Law and Terms are, and they are already taught (they are both forms of what you call “strong juxtaposition”, but note that they are 2 different rules, so you can’t cover them both with a single rule like “strong juxtaposition”. That’s where the people who say “implicit multiplication” are going astray - trying to cover 2 rules with one).

See this part of my comment… Weak juxtaposition provides better benefits because it has less rules (and is thusly simpler)

Yep, saw it, and weak juxtaposition would break the existing rules of Maths, such as The Distributive Law and Terms. (Re)learn the existing rules, that is the point of the argument.

citation needed

Well that part’s easy - I guess you missed the other links I posted. Order of operations thread index Text book references, proofs, the works.

this issue isn’t a mathematical one, but a grammatical one

Maths isn’t a language. It’s a group of notation and rules. It has syntax, not grammar. The equation in question has used all the correct notation, and so when solving it you have to follow all the relevant rules.

Nope. Teachers can decide how they teach. They cannot decide what they teach. The have to teach whatever is in the curriculum for their region.

Yes, teachers have certain things they need to teach. That doesn’t prohibit them from teaching additional material.

That’s because neither of those is a rule of Maths. The Distributive Law and Terms are, and they are already taught (they are both forms of what you call “strong juxtaposition”, but note that they are 2 different rules, so you can’t cover them both with a single rule like “strong juxtaposition”. That’s where the people who say “implicit multiplication” are going astray - trying to cover 2 rules with one).

Yep, saw it, and weak juxtaposition would break the existing rules of Maths, such as The Distributive Law and Terms. (Re)learn the existing rules, that is the point of the argument.

Well that part’s easy - I guess you missed the other links I posted. Order of operations thread index Text book references, proofs, the works.

You argue about sources and then cite yourself as a source with a single reference that isn’t you buried in the thread on the Distributive Law? That single reference doesn’t even really touch the topic. Your only evidence in the entire thread relevant to the discussion is self-sourced. Citation still needed.

Maths isn’t a language. It’s a group of notation and rules. It has syntax, not grammar. The equation in question has used all the correct notation, and so when solving it you have to follow all the relevant rules.

You can argue semantics all you like. I would put forth that since you want sources so much, according to Merriam-Webster, grammar’s definitions include “the principles or rules of an art, science, or technique”, of which I think the syntax of mathematics qualifies, as it is a set of rules and mathematics is a science.

That doesn’t prohibit them from teaching additional material

Correct, but it can’t be something which would contradict what they do have to teach, which is what “weak juxtaposition” would do.

a single reference

I see you didn’t read the whole thread then. Keep going if you want more. Literally every Year 7-8 Maths textbook says the same thing. I’ve quoted multiple textbooks (and haven’t even covered all the ones I own).

mathematics is a science

Actually you’ll find that assertion is hotly debated.

Correct, but it can’t be something which would contradict what they do have to teach, which is what “weak juxtaposition” would do.

Citation needed.

I see you didn’t read the whole thread then. Keep going if you want more. Literally every Year 7-8 Maths textbook says the same thing. I’ve quoted multiple textbooks (and haven’t even covered all the ones I own).

If I have to search your ‘source’ for the actual source you’re trying to reference, it’s a very poor source. This is the thread I searched. Your comments only reference ‘math textbooks’, not anything specific, outside of this link which you reference twice in separate comments but again, it’s not evidence for your side, or against it, or even relevant. It gets real close to almost talking about what we want, but it never gets there.

But fine, you reference ‘multiple textbooks’ so after a bit of searching I find the only other reference you’ve made. In the very same comment you yourself state “he says that Stokes PROPOSED that /b+c be interpreted as /(b+c). He says nothing further about it, however it’s certainly not the way we interpret it now”, which is kind of what we want. We’re talking about x/y(b+c) and whether that should be x/(yb+yc) or x/y * 1/(b+c). However, there’s just one little issue. Your last part of that statement is entirely self-supported, meaning you have an uncited refutation of the side you’re arguing against, which funnily enough you did cite.

Now, maybe that latter textbook citation I found has some supporting evidence for yourself somewhere, but an additional point is that when providing evidence and a source to support your argument you should probably make it easy to find the evidence you speak of. I’m certainly not going to spend a great amount of effort trying to disprove myself over an anonymous internet argument, and I believe I’ve already done my due diligence.

Citation needed.

So you think it’s ok to teach contradictory stuff to them in Maths? 🤣 Ok sure, fine, go ahead and find me a Maths textbook which has “weak juxtaposition” in it. I’ll wait.

Your comments only reference ‘math textbooks’, not anything specific

So you’re telling me you can’t see the Maths textbook screenshots/photo’s?

outside of this link which you reference twice in separate comments but again, it’s not evidence for your side, or against it, or even relevant

Lennes was complaining that literally no textbooks he mentioned were following “weak juxtaposition”, and you think that’s not relevant to establishing that no textbooks used “weak juxtaposition” 100 years ago?

We’re talking about x/y(b+c) and whether that should be x/(yb+yc) or x/y * 1/(b+c).

It’s in literally the first textbook screenshot, which if I’m understanding you right you can’t see? (see screenshot of the screenshot above)

you have an uncited refutation of the side you’re arguing against, which funnily enough you did cite.

Ah, no. Lennes was complaining about textbooks who were obeying Terms/The Distributive Law. His own letter shows us that they all (the ones he mentioned) were doing the same thing then that we do now. Plus my first (and later) screenshot(s).

Also it’s in Cajori, but I didn’t find it until later. I don’t remember what page it was, but it’s in Cajori and you have the reference for it there already.

you should probably make it easy to find the evidence you speak of

Well I’m not sure how you didn’t see all the screenshots. They’re hard to miss on my computer!

P.S. if you DID want to indicate “weak juxtaposition”, then you just put a multiplication symbol, and then yes it would be done as “M” in BEDMAS, because it’s no longer the coefficient of a bracketed term (to be solved as part of “B”), but a separate term.

6/2(1+2)=6/(2+4)=6/6=1

6/2x(1+2)=6/2x3=3x3=9

My years out of school has made me forget about how division notation is actually supposed to work and how genuinely useless the ÷ and / symbols are outside the most basic two-number problems. And it’s entirely me being dumb because I’ve already written problems as 6÷(2(1+2)) to account for it before. Me brain dun work right ;~;

There’s no forms consensus on which one is correct. To avoid misunderstanding mathematicians use a horizontal bar.

Only if it’s a fraction. If it’s 2 separate terms then you use whatever your country uses for division - obelus or colon or whatever. They have to be 2 separate things, otherwise how would you write to divide by a fraction?

Interesting that Excel sees =6/2(1+2) as an invalid formula and will not calculate it (at least on mobile). =6/2*(1+2) returns 9 because it’s executing the division and multiplication left to right (6/2=3*3=9).

Google Sheets (mobile) does’t like it either and returns an error. =6/2*(1+2) also returns “9”.

Excel and Google are both wrong. In fact, Microsoft excels 😂in this area, with Excel, the Windows calculator, and MathSolver all getting it wrong in different ways! dotnet.social/@SmartmanApps/111164851485070719

Starting a new comment thread (I gave up on reading all of them). I’m a high school Maths teacher/tutor. You can read my Mastodon thread about it at Order of operations thread index (I’m giving you the link to the thread index so you can just jump around whichever parts you want to read without having to read the whole thing). Includes Maths textbooks, historical references, proofs, memes, the works.

And for all the people quoting university people, this topic (order of operations) is not taught at university - it is taught in high school. Why would you listen to someone who doesn’t teach the topic? (have you not wondered why they never quote Maths textbooks?)

#DontForgetDistribution #MathsIsNeverAmbiguous

I’m curious if you actually read the whole (admittedly long) page linked in this post, or did you stop after realizing that it was saying something you found disagreeable?

I’m a high school Maths teacher/tutor

What will you tell your students if they show you two different models of calculator, from the same company, where the same sequence of buttons on each produces a different result than on the other, and the user manuals for each explain clearly why they’re doing what they are? “One of these calculators is just objectively wrong, trust me on this, #MathsIsNeverAmbiguous” ?

The truth is that there are many different math notations which often do lead to ambiguities.

In the case of the notation you’re dismissing in your (hilarious!) meme here, well, outside of anglophone high schools, people don’t often encounter the obelus notation for division at all except for as a button on calculators. And there its meaning is ambiguous (as clearly explained in OP’s link).

Check out some of the other things which the “÷” symbol can mean in math!

#MathNotationsAreOftenAmbiguous

did you stop after realizing that it was saying something you found disagreeable

I stopped when he said it was ambiguous (it’s not, as per the rules of Maths), then scanned the rest to see if there were any Maths textbook references, and there wasn’t (as expected). Just another wrong blog.

What will you tell your students if they show you two different models of calculator, from the same company

Has literally never happened. Texas Instruments is the only brand who continues to do it wrong (and it’s right there in their manual why) - all the other brands who were doing it wrong have reverted back to doing it correctly (there’s a Youtube video about this somewhere). I have a Sharp calculator (who have literally always done it correctly) and most of my students have Casio, so it’s never been an issue.

trust me on this

I don’t ask them to trust me - I’m a Maths teacher, I teach them the rules of Maths. From there they can see for themselves which calculators are wrong and why. Our job as teachers is for our students to eventually not need us anymore and work things out for themselves.

The truth is that there are many different math notations which often do lead to ambiguities

Not within any region there isn’t. e.g. European countries who use a comma instead of a decimal point. If you’re in one of those countries it’s a comma, if you’re not then it’s a decimal point.

people don’t often encounter the obelus notation for division at all

In Australia it’s the only thing we ever use, and from what I’ve seen also the U.K. (every U.K. textbook I’ve seen uses it).

Check out some of the other things which the “÷” symbol can mean in math!

Go back and read it again and you’ll see all of those examples are worded in the past tense, except for ISO, and all ISO has said is “don’t use it”, for reasons which haven’t been specified, and in any case everyone in a Maths-related position is clearly ignoring them anyway (as you would. I’ve seen them over-reach in Computer Science as well, where they also get ignored by people in the industry).

Has literally never happened. Texas Instruments is the only brand who continues to do it wrong […] all the other brands who were doing it wrong have reverted

Ok so you’re saying it never happened, but then in the very next sentence you acknowledge that you know it is happening with TI today, and then also admit you know that it did happen with some other brands in the past?

But, if you had read the linked post before writing numerous comments about it, you’d see that it documents that the ambiguity actually exists among both old and currently shipping models from TI, HP, Casio, and Canon, today, and that both behaviors are intentional and documented.

There is no bug; none of these calculators is “wrong”.

The truth is that there are many different math notations which often do lead to ambiguities

Not within any region there isn’t.

Ok, this is the funniest thing I’ve read so far today, but if this is what you are teaching high school students it is also rather sad because you are doing them a disservice by teaching them that there is no ambiguity where there actually is.

If OP’s blog post is too long for you (it is quite long) i recommend reading this one instead: The PEMDAS Paradox.

In Australia it’s the only thing we ever use, and from what I’ve seen also the U.K. (every U.K. textbook I’ve seen uses it).

By “we” do you mean high school teachers, or Australian society beyond high school? Because, I’m pretty sure the latter isn’t true, and I’m skeptical of the former. I thought generally the ÷ symbol mostly stops being used (except as a calculator button) even before high school, basically as soon as fractions are taught. Do you have textbooks where the fraction bar is used concurrently with the obelus (÷) division symbol?

Here is an alternative Piped link(s):

Piped is a privacy-respecting open-source alternative frontend to YouTube.

I’m open-source; check me out at GitHub.

Ok so you’re saying it never happened, but then in the very next sentence you acknowledge that you know it is happening with TI today

You asked me what I do if my students show me 2 different answers what do I tell them, and I told you that has never happened. None of my students have ever had one of the calculators which does it wrong.

that both behaviors are intentional and documented

Correct. I already noted earlier (maybe with someone else) that the TI calculator manual says that they obey the Primary School order of operations, which doesn’t work with High School order of operations. i.e. when the brackets have a coefficient. The TI calculator will give a correct answer for 6/(1+2) and 6/2x(1+2), but gives a wrong answer for 6/2(1+2), and it’s in their manual why. I saw one Youtuber who was showing the manual scroll right past it! It was right there on screen why it does it wrong and she just scrolled down from there without even looking at it!

none of these calculators is “wrong”.

Any calculator which fails to obey The Distributive Law is wrong. It is disobeying a rule of Maths.

there is no ambiguity where there actually is.

There actually isn’t. We use decimal points (not commas like some European countries), the obelus (not colon like some European countries), etc., so no, there is never any ambiguity. And the expression in question here follows those same notations (it has an obelus, not a colon), so still no ambiguity.

i recommend reading this one instead: The PEMDAS Paradox

Yes, I’ve read that one before. Makes the exact same mistakes. Claims it’s ambiguous while at the same time completely ignoring The Distributive Law and Terms. I’ll even point out a specific thing (of many) where they miss the point…

So the disagreement distills down to this: Does it feel like a(b) should always be interchangeable with axb? Or does it feel like a(b) should always be interchangeable with (ab)? You can’t say both.

ab=(axb) by definition. It’s in Cajori, it’s in today’s Maths textbooks. So a(b) isn’t interchangeable with axb, it’s only interchangeable with (axb) (or (ab) or ab). That’s one of the most common mistakes I see. You can’t remove brackets if there’s still more than 1 term left inside, but many people do and end up with a wrong answer.

By “we” do you mean high school teachers, or Australian society beyond high school?

I said “In Australia” (not in Australian high school), so I mean all of Australia.

Because, I’m pretty sure the latter isn’t true

Definitely is. I have never seen anyone here ever use a colon to mean divide. It’s only ever used for a ratio.

Do you have textbooks where the fraction bar is used concurrently with the obelus (÷) division symbol?

All my textbooks use both. Did you read my thread? If you use a fraction bar then that is a single term. If you use an obelus (or colon if you’re in a country which uses colon for division) then that is 2 terms. I covered all of that in my thread.

EDITED TO ADD: If you don’t use both then how do you write to divide by a fraction?

What’s especially wild to me is that even the position of “it’s ambiguous” gets almost as much pushback as trying to argue that one of them is universally correct.

Last time this came up it was my position that it was ambiguous and needed clarification and had someone accuse me of taking a prescriptive stance and imposing rules contrary to how things were actually being done. How asking a person what they mean or seeking clarification could possibly be prescriptive is beyond me.

Bonus points, the guy telling me I was being prescriptive was arguing vehemently that implicit multiplication having precedence was correct and to do otherwise was wrong, full stop.

When I went to college, I was given a reverse Polish notation calculator. I think there is some (albeit small) advantage of becoming fluent in both PEMDAS and RPN to see the arbitrariness. This kind of arguement is like trying to argue linguistics in a single language.

Btw, I’m not claiming that RPN has any bearing on the meme at hand. Just that there are different standards.

This comment is left by the HP50g crew.

It would be better if we just taught math with prefix or postfix notation, as it removes the ambiguity.

My only complaint is the suggestion that engineers like to be clear. My undergrad classes included far too many things like

2 cos 2 x sin yI’d say engineers like to be exact, but they like being lazy even more